After the defeat of Japan in World War 2 following on from the two Atomic Bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan had to withdraw all its Forces that were spread across the Far East. The largest quantity of Japanese soldiers who returned came from China and Korea. There always was a huge amount of hatred between Japan and Korea. Japan had invaded Korea in 1910 and stayed in control until August 1945 when Hiroshima was obliterated by the Atom Bomb.

At the time, unknown to the United States, a spy called Klaus Fuchs stole the Blueprints of the Atomic Bomb and passed them on to Russia. China wanted a deal with Russia which meant that they would both have the Bomb. World tension was seriously high at that time and, to make matters worse, China supplied arms and ammunition to North Korea in an attempt to take over South Korea in a civil war, so creating a communist state. They got as far as the outskirts of Seoul but large US Forces landed at In-Chon and stopped the North Korean advance into the city. The US had seen the invasion as the advance of Communism ‘that must be stopped’. Britain also sent 75,000 troops to defend S. Korea using both Regular Troops and National Service men. Australia and New Zealand joined in and this collection of men from the British Empire became known as the 1st Commonwealth Division. Using these United Nations troops was successful and the N. Koreans were driven back as far as the 38th parallel but as they came near to the Yalu River, China entered the war with 200,000 soldiers. They marched by night, undetected, and set up a trap for the US Army Divisions in a valley around a lake called the Chosin Reservoir. US Marines built road blocks but the Chinese launched a major assault and ‘all hell broke loose.

Although they were shot even multiple times, the Chinese ran forward. The US soldiers felt ill equipped for the type of combat that they faced. The US anti-tank units spent days crawling up mountain sides using their 75mm recoilless rifles to bust Chinese bunkers. This allowed most Marines to move eastwards and south out of the trap. However 4,000 US troops fought towards the north to secure the exit of 10,000 Marines trapped in the Chosin Valley. Altogether 25,000 UN troops were involved in the battle with most companies reduced from 160 down to 30. Having extricated their survivors, the US troops were faced with a 70 mile march down a winding, icy mountain road Funchilin Pass. The road was littered with burnt out vehicles, broken equipment, redundant gear and dead Chinese soldiers. This march was achieved in temperatures of 40 below zero. The Chinese blew up a crucial bridge over a treacherous mountain gorge, cutting off the US evacuation route but US air power saved the day by dropping two portable, pre-fabricated Bailey Bridges via huge parachutes. Without these bridges the US soldiers would all have been captured.

The US Marines had nothing good to say about their General Macarthur, who, after the Chosin Valley battle wanted to press on and expand into China. Macarthur was ultimately relieved of his Command by President Truman who was opposed to the idea. He remained committed to a ‘limited war in Korea’.

All Un soldiers were badly equipped for the Korean climate. In order to fire their weapons, they had to take off their clumsy mittens. Weapons failed to fire, car batteries went dead and lubricants froze in artillery guns and vehicles. Even the Blood Plasma used in First Aid Stations, as in World War 2, froze to solid blocks in the N. Korean winter. The losses at Chosin Valley were painfully high. The estimated 18,000 casualties included 2,500 killed in action, 5,000 wounded and 8,000 suffered frostbite.

The Chinese were much worse off (they were even happy to be captured). Their feet were blocks of ice. Most of them had been hastily mobilised from Manchuria for deployment in Korea. They had no winter clothing or sufficient food. The Chinese leadership made crucial mistakes that cost lives and gave UN forces time to retreat. Some 30,000 Chinese soldiers perished from cold alone along with around 20,000 combat casualties. Maps published after the war would show a defeat for US troops in the Chosin Valley. Britain lost 1,100 soldiers killed in action with five times that number wounded.

However, all UN troops fought exceptionally hard because they knew what awaited them if they were captured by the Chinese or N. Koreans. POW’s were tortured and frequently left for days in solitary bamboo cages with little or no food.

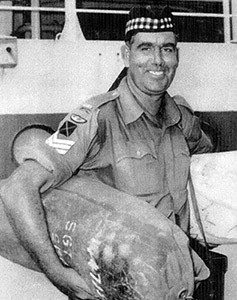

Perhaps it was these thoughts that drove British soldier, Bill Speakman to the actions that earned him the Victoria Cross in Korea. Bill was born and brought up in Altrincham, Cheshire. He was 24 years old and a Private in the Black Watch, attached to the 1st Battalion, King’s Own Scottish Borderers when the following deed took place according to his Citation.

On 4th November 1951 in Korea, when the section holding the left shoulder of the company’s position had been seriously depleted by casualties and was being overrun by the enemy, Bill, on his own initiative, filled his pockets with grenades going forward and pelting the Chinese with the grenades. He was a formidable character, 6ft 5inches in height and roaring as he threw the grenades. Having used all his stock of grenades, he returned for more. Inspired by his actions six men joined him in collecting a pile of grenades and followed him in a series of charges. He broke up several enemy attacks, causing heavy casualties and in spite of being wounded in his leg and shoulder continued to lead charge after charge. Such was the ferocity of the fighting that they ran low in ammunition, resorting to throwing stones and ration tins. The enemy was kept at bay long enough to enable his Company to withdraw safely.

The Press of the time nicknamed him the ‘beer bottle VC’, something that he disliked since it suggested that he and his colleagues drank beer while on duty. The beer was in fact used to cool gun barrels. Although his Award was made by King George V1, Bill was the first Victoria Cross invested by Queen Elizabeth 2. He later achieved the rank of Sergeant and served in Malaya and Borneo (with the SAS). When he retired Bill became a Chelsea Pensioner and lived at the Royal Hospital. He died in June 2018 and his ashes are buried in the UN Cemetery, South Korea.

Although as mentioned earlier, Bill spent his youth in Altrincham, near Manchester but to be precise he was bred in the tiny village of Timperley. Little was the author to know it but I spent my 2 weeks annual holiday with my cousin in that exact spot. No, I regrettably did not meet Bill, but what a co-incidence!

“Of all the villages in all the world”………………………………………………….